Other ways to protect yourself on the web: GDPR, CCPA, and AdChoices

Because of regulations like Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), more and more websites have been forced to let visitors control the use of cookies and other trackers at each site. Many multinational companies provide the same options to users outside the GDPR and CCPA jurisdictions for simplicity’s sake. Because blocking cookies in a browser is typically an all-or-nothing proposition, it’s often not a realistic option — after all, some websites need cookies to function in the ways you want, such as to sign you in automatically when you come back.

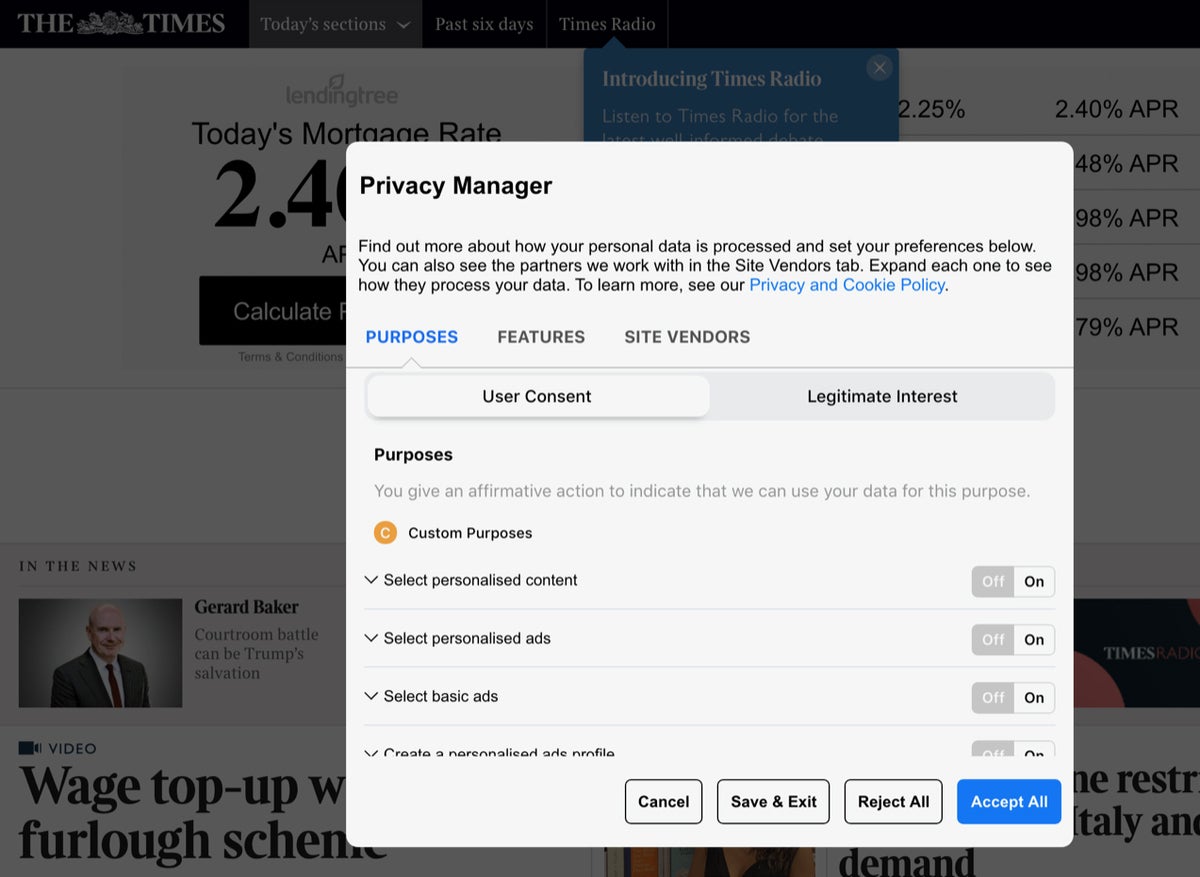

That’s where using the cookie controls mandated by GDPR and CCPA can help, if available to you. If you go to a European website, you will almost certainly get a GDPR consent pop-up, and there you can see the cookies that the site wants to use. The marketing cookies are the ones to pay attention to; often, there will be dozens even hundreds of cookies listed from companies you’ve never heard of.

Note: Ad blockers, content blockers, and other such privacy tools ironically can suppress the consent forms needed to use CCPA or GDPR on various sites. Also, if your browser is set to block third-party cookies (the unchangeable default in Safari 14 and later), it often won’t save your privacy cookie settings on sites (because typically a third party is used to manage such cookies) — that’s why you may be asked to set privacy settings every time you visit a site. Ironically, that can lead to permission fatigue, where you just click OK or Accept rather than go through all the settings each time.

IDG

IDG

Under GDPR, EU residents can control which types of cookies are enabled on the sites they visit, and some websites let non-EU residents use the same controls as well. Here are the Times of London’s cookie controls.

IDG

IDG

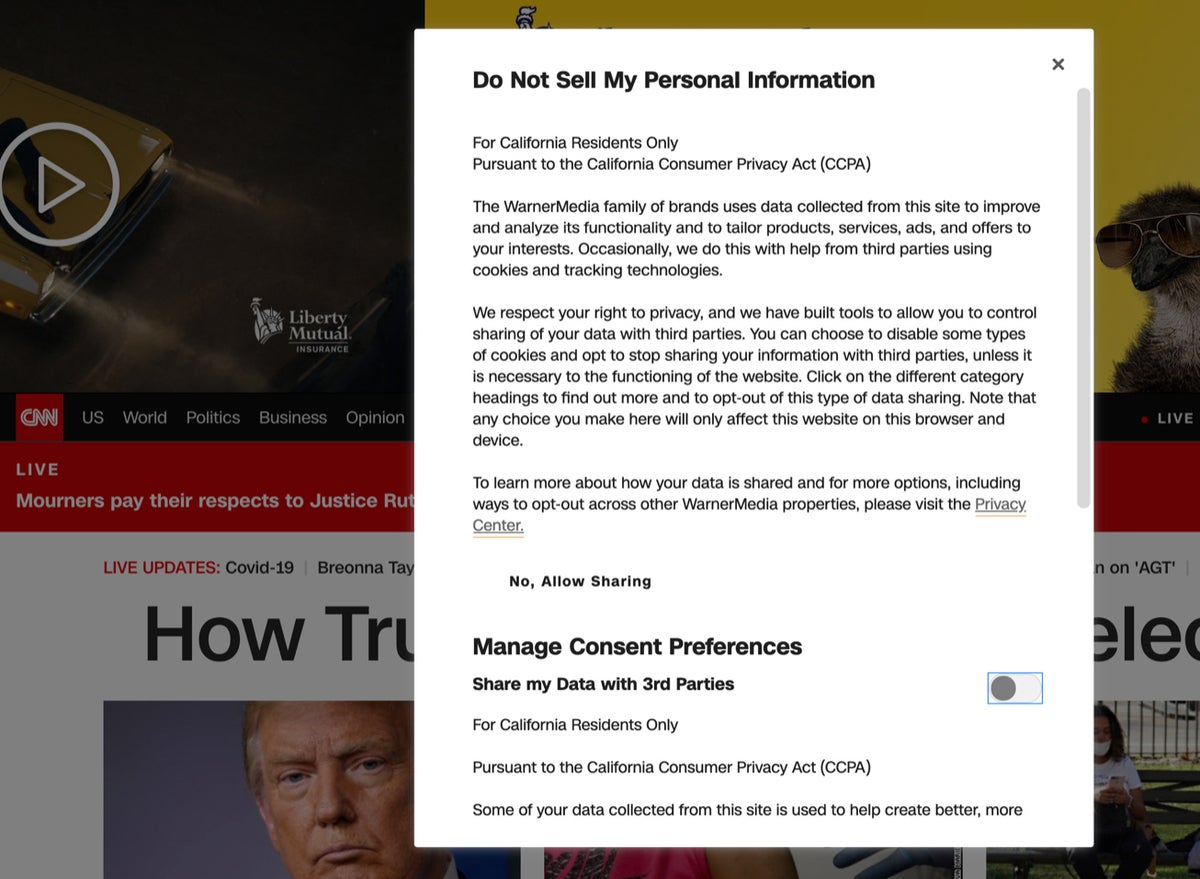

Under the CCPA, the Do Not Sell My Personal Information control lets California residents opt out of some data collection.

Some cookies “follow” you from site to site, so they can display the same ads wherever you go based on your purported interest in something, such as what you searched for in Amazon or in a search engine. Other cookies go further, tracking your behavior and interests as you surf the web to help build a profile of you.

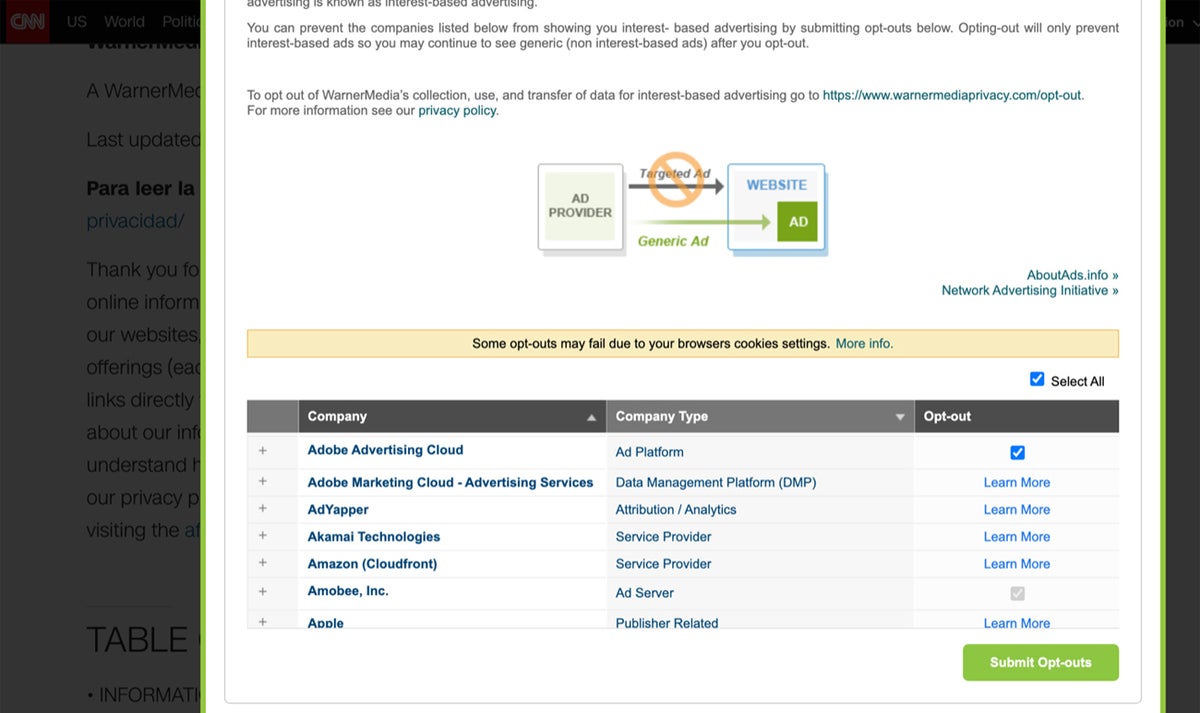

A lot of these cookies come from the ad networks that websites use, so the website publisher itself has no idea who these cookies come from either. Ad networks also link to other ad networks, so no one may really understand who is tracking users on a given site. You can easily have dozens, even hundreds of advertisers on a given site trying to silently install cookies in your browser.

Rather than decide individually which to allow, just block them all. If enough people did that, maybe publishers and ad networks would actually manage these “partners” and remove the nefarious ones. Look for controls over such cookies, such as from an AdChoices link or Cookie Policy link. And even blocking them all per site is arduous, as you must go to each site you visit to set the controls, assuming it even offers them — there’s no universal way to set advertiser privacy settings, other than the heavy-handed approach of using ad blockers.

IDG

IDG

Most commercial websites quietly install advertiser and other commercial cookies in your browser. Some websites, such as CNN, let you control which of the dozens, even hundreds of advertisers and ad networks can install cookies in your browser. Prepare to scroll through all the options — or simply reject them all if presented that option.

Privacy steps to take outside the browser

If you really want to stay private, you shouldn’t use the internet. But of course that is not possible. So what can you do beyond what your browser allows? Here are the steps you can take for your other internet activities, both web-based and app-based — those other internet tools are more powerful spies than your browser itself.

The goal is to limit what you share and make it harder for those tracking companies to get a full view of your activities.

- Don’t use social networks. If you must use them, share as little as possible. Use their privacy settings, but don’t think for a minute that means you’re no longer tracked. Facebook is particularly notorious for unsavory, unacknowledged use of user data — even if you don’t have an account and simply visit a Facebook page.

- Don’t use voice assistants like Alexa or Siri. They collect a lot of data about you. (Apple has long promoted its privacy focus, and it does appear that Apple largely doesn’t resell the massive data it collects on you. But recent versions of macOS and iOS introduced a service called Siri Suggestions that analyze your activities to make recommendations — the kinds of things Google, Facebook, and others have done for years. That data is all going to Apple, and that’s discomforting. We’ve seen Apple bows to anti-privacy requests in some countries, so even if Apple is more respectful of your privacy than most data-gathering tech giants, there is a risk.)

- Turn off “helpful” tracking features like Google Assistant, Siri Suggestions, and their equivalents from Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, and anyone else on your mobile devices, web services, and computers (and don’t forget to turn off the advertising ID in the General privacy settings in Windows 10 and 11).

- Turn off location services for any app or website that doesn’t truly need it. For apps like browsers, do so in Settings > Privacy in Windows 10 and 11, macOS’s Privacy & Settings system preference, iOS’s Location Services controls in Settings, and Android’s Location control in Settings. If you need location services enabled for some websites, use the per-site controls when available in that browser to do so, leaving location services disabled for the rest by default.

- Go through the other privacy settings as well on each device you have, and limit access to your activities and information as much as you can.

- Avoid signing in at online stores when researching products in a browser or shopping app; sign in only when you’ve decided what to buy, so the retailer can’t track your research activities.

- Take advantage of laws like California’s CCPA or Europe’s GDPR when you can, to delete your data or restrict its use, not just manage cookies. Likewise, regularly purge your data at Google and other services that extensively track you.

- Consider using a virtual private network, but be careful. The free ones are making money somehow, and your data is almost certainly that “somehow.”

- Consider using CloudFlare’s 1.1.1.1 service, which is a proxy DNS server that directs your web traffic through CloudFlare rather than through your internet service provider. ISPs often collect your search traffic and sell the resulting profiles to advertisers and other commercial interests. CloudFlare is a business, of course — it manages internet traffic for publishers, vendors, government agencies, and more — but it seems to have less troublesome uses for the data it collects than the ISPs do. And I’m more comfortable with 1.1.1.1 than with free VPNs. Remember: Nothing is truly free, it’s just what the actual payment is.

- If you use 1.1.1.1, set it up in your router so all your networked devices are automatically protected; just set your primary DNS to 1.1.1.1 and secondary DNS to 1.0.0.1). Doing so also means on mobile devices you don’t have to disable the 1.1.1.1 pseudo-VPN to use a corporate VPN. On desktop computers, 1.1.1.1 doesn’t use a pseudo-VPN, so there’s no conflict with corporate VPNs there. Still, for when you are traveling and away from your protected router, you may want to set up 1.1.1 1 on your computers and mobile devices, too. On a computer, configure the primary DNS to 1.1 1.1 and secondary DNS to 1.0.0.1 in the operating system’s network settings. (Once set, you can leave it as is.) On a mobile device, install the 1.1.1.1 app from the App Store, and turn it on when traveling — just remember you must turn off the app to use a corporate VPN, if your device doesn’t do that automatically when you try to switch VPNs.

They might still be able to track you through other means, of course, but why make it easy? You can’t be completely private, but you can create some shadows around yourself.

This article was originally published in November 2020 and most recently updated in October 2022.

More privacy tips

- How to protect your privacy in Windows 10

- How to stay as private as possible on the Mac

- The ultimate guide to privacy on Android

- How to stay as private as possible on Apple’s iPad and iPhone

- How to go incognito in Chrome, Edge, Firefox, and Safari